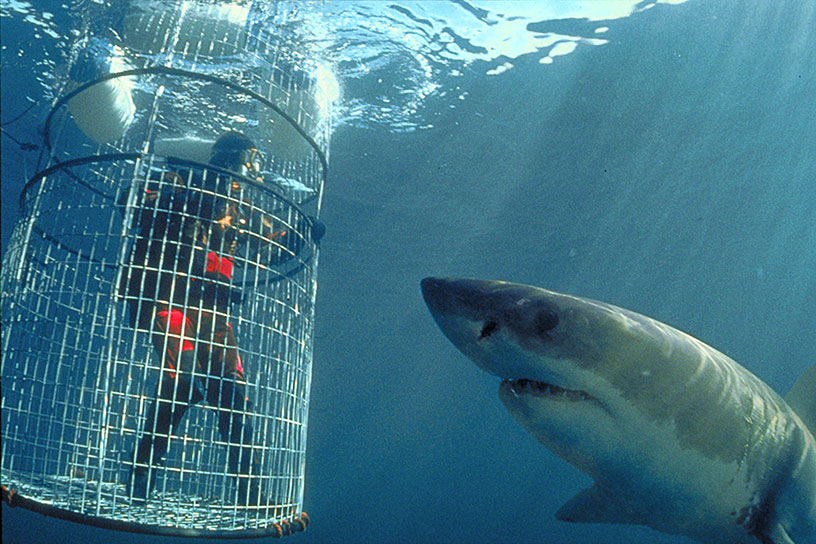

I was in a metal cage under a boat 18 feet underwater on the sandy bottom of Dyer Island off Gansbaai, South Africa. As the great white passed over my head, it cast a dark shadow over me.

Andre Hartman, the legendary great white shark wrangler, was attracting the sharks to a diving platform. He was teasing them. He took the bait away every time the sharks showed up for a handout so they would return again and they did.

After missing the bait a few times, one shark changed its tactic. Rather than swimming towards the bait on top of the water, the shark began to skim along the sandy bottom of “Shark Alley”. I was surprised to see the shark arrive at my eye level, turn abruptly 90 degrees in front of the cage and swim towards the surface. The shark ignored my presence and my bubbles. I could see the silhouette of the bait in Andre’s hand. So could the shark! The next time the shark approached, I climbed on top of the cage and stood in front of the advancing shark. I was ready to take my shot! The shark flashed vertically through the water. I raised the camera to my eyes as a shield. I missed this photo opportunity mostly because of excitement and fear.

Great White Shark arriving at the cage

For the next dive I had a better understanding of what to expect. Andre, the crew and I coordinated our efforts and I got the image I wanted. Excited and pumped up with adrenalin Andre and I started goading each other for the next adventure.

The ensuing challenge was to photograph a great white shark with its jaws wide open underwater. Andre was leading the action, baiting the surface water for incoming sharks. As a large shark approached, inches from the bait, Andre did something amazing. With nerves of steel, he removed the bait with one hand and placed his other hand over the shark’s snout…putting the shark into a trance state! Thus the great white froze in its place. It hung vertically, jaws wide open above water, while Andre’s palm covered its Ampolla de Lorenzini. The shark remained motionless with its head out of the water for the next 15 to 20 seconds.

Tonic-immobility

Excited by our daring pursuits, we decided to push our luck further. I noticed from the time Andre removed his hand to the moment the shark was submerged, there was a brief opportunity to get my shot… a fleeting instant the shark’s jaws would be open underwater.

I lay on the diving platform waiting for the moment Andre touched the shark and it opened its jaws. As he removed his hand, I placed my camera underwater and watched the shark submerge. My hands held the camera inches from its jaws, wide open with all its formidable rows of teeth. It was worth the risk to get the image.

Open-Jaws-Under-Water

In South Africa, even during prime time for the great white, weather is problematic. It is often windy on the surface with poor visibility underwater. The challenge in getting images is to calculate these risks while engaging with exiting animal behavior under very poor photographic conditions.

One evening, Andre and I were talking about shark behavior. We were watching our video clips and images and as we watched the idea came to us simultaneously – what if we dived out of the cage?

After short hesitation, Andre agreed on one condition. He said visibility must be good, at least 30 feet. I deferred to him because of my respect for his experience. But what I did not know is that it would take us 27 days of waiting for the visibility to improve. We kept ourselves busy telling stories, visiting bars, watching TV, playing soccer with the locals and searching for cobras in the mountains around Gansbaai. We visited farms and took pictures of exotic flowers. In short, we were killing time waiting for our next adventure. Our kind of camaraderie is rare. We both knew this was an important opportunity and we did not want to miss it. We waited until August 2, 1997 to get what we wanted: 30 feet visibility underwater. We raced to prepare our gear, boat and assemble our team for briefing. When we told the crew our plan to dive out of the cage they stared at us in disbelief. Eventually, the crew was excited to help us and be part of our exploit.

The sea was calm as we left port. Andre was manning the boat and I was alone with my thoughts. There were so many emotions racing through me: fear, excitement, anxiety and determination. What if the shark bit Andre? Or me? I had to chase all these thoughts out of my mind and trust my own experience. I could count only on Andre and myself. With these thoughts in mind, I started to relax and feel the wind against my skin. I could smell the strong, salty scent of the ocean and kelp. I could hear the seals barking. I felt ready to dive.

When we dropped anchor, I rushed to help Andre and the crew roll the circular cage into the water. Andre started chumming the water and the sharks appeared about 20 minutes later. Andre looked at me and asked “Are you ready? I’m going in”. I followed him with trepidation.

As soon as we hit the water, we dived down and hugged the outside of the cage that was resting at about 35 feet on a rocky bank. Our eyes were fixed on the 5-meter shark circling around the boat just above our heads.

Visibility was good, but because the water was cold its density made it appear less so. The temperature was about 52F (12C) and I could feel my body shiver despite the 7mm wetsuit.

We crouched on the rocky ledge by the cage and watched the shark circling on the surface. After a few minutes, which seemed like an eternity, the shark left and did not return. Andre and I went forward with our plan. Andre took the bait from the cage. I reached for my camera, ready for action.

Together we swam away from the cage, watching each other’s backs and scanning for sharks. We swam close to each other, our tanks banging and our fins crossing a few times. We were tense and did not know what to expect.

Andre found a rock cropping to hide the bait. He unwrapped the bait, squeezed it to release its scent and placed it under a rock. We retreated about 10 feet and waited. Soon, a smaller 14 feet great white approached the bait.

To our surprise, as the shark neared the bait it slowed down, raised its snout inches above the rock and continued toward us. Andre quickly put his hand over my head and pushed us flat against the rock. The shark passed us as though we did not exist.

After few minutes, Andre swam back to the rock and again squeezed the bait. In less than a minute, we saw the shark over our head diving down, speeding toward the bait. The shark grabbed the bait and twisted it violently from under the rock. Then it began to ascend towards the light.

Andre followed the shark toward the surface while I trailed behind them. The shark was silhouetted against the sun. The sunlight reflected off Andre’s mask as he reached out to the great white. I held my breath to avoid creating bubbles. This time I got the image I wanted: one that represents the courage and knowledge of how to be in the water peacefully with a great white.

Outside the cage

Few sights in the wilderness are spectacular as a 4000-pound (an average weight) great white breaching out of the water. It happened off Seal Island, (ring of death) False Bay, South Africa.

It was dark and cold when we left in our boat. After 40 minutes, we knew we reached the island because we heard the noise and smelled the stench of over 60,000 seals, during the peak season.

We arrived at dawn. There was just enough light to see the outline of the island. The boat slowed and we took out our cameras as my four clients selected their shooting position.

Just as we thought we were ready, our skipper Essie got his engine into gear and start moving fast west of the Island. He pointed through his window. At first, I did not see anything. Then something jumped from of the water with big splash. A second later another thing jumped out of the water with a smaller splash. Essy quickly pointed out the first splash was the shark and the second a lucky seal which got away.

None of us got that shot. Now each of us was in a different position around the boat, hoping to capture the next shark attack. Staying on deck, we were well dressed for cold and the wind: beanie, scarf, heavy jacket, gloves etc. Our breath created clouds in front of our eyes. A yell came from the port side and Essy turned the boat around—too late again. W saw only splashes. The sky was turning blue but the sun had not yet risen.

Seeing so many sharks breaching, we were excited and determined despite the cold. There were at least three attacks by sharks on seal pods as they left the island to hunt.

The sun began to shine. Essie stopped the boat to prepare a seal dummy made out of rubber. A dummy floating behind a vessel is designed to attract sharks and provide a point on which our cameras can focus. Hopefully, this improves our chances of capturing one of these breaches on still or video. Essy tossed the dummy overboard which was attached to the boat by 25 ft. long, 40-pound weight fishing line.

While the dummy floated behind the boat, Essy start cruising slowly around Seal Island. While the dummy floated behind the boat, Essie start cruising slowly around Seal Island, along what is called the “Ring of Death”. The surrounding of Seal Island is known for shark attacks on seals. The Island surrounded by rock cliff plunging to 40 – 60 feet deep. This kind of underwater topography is classic environment for great white to ambush the seals. Great white patrol the island in the deep water, waiting for seals pods as they leave the island or return from their fishing ground. This happened only during the low light condition of the day, in the early morning hours or late afternoon before dark. During which time light does not reach the deep water, great white see the seals silhouette on the surface, but the seals can not see the shark ambushing in the deep water. Once the shark identifies its prey on the surface it propel itself vertically in full speed toward the surface for the kill. Knowing that all four of us sat along the dive platform in great anticipation, cameras in our hands.

All four of us sat along the dive platform, cameras in our hands.

The sun was up and the sky was bluer. The sea was moderate: about three foot waves and our boat rocked from side to side. It was hard for us to stabilize ourselves with heavy cameras and long lenses (70 – 200mm). Every few minutes, we had to let our hands and eyes rest. Each leg of our course as we went back and forth in front of the island took about 30 minutes.

Suddenly we had a first breach on the dummy! Of course, we all missed it. There was no way to know when a shark would want to bite the dummy seal. However, at least we knew where it might happen. I told my guests, we could only get the image with determination and patience.

After about 90 minutes everyone was exhausted. Although we saw four more breaches, we got nothing. We were drained, fighting our boats sway, engine fumes and discouragement at missing all these amazing breaches.

It was past 8am and the sun was getting higher. According to Essy, shark action would stop any minute. I asked Essy for one more lap, 30 minutes longer.

Two of my guests gave up and the other two joined me on the platform. Totally drenched from the waves, my lungs full of diesel fumes, I had only one thing in my mind—I will get it next time. In my mind, I saw a shark breaching again and again. Worse, I kept nodding off behind my camera. Each time a wave soaked me I woke up. Nevertheless, I kept the camera against my eye. I held the camera vertically rather than in the classic horizontal position. Usually, all breaching images are taken horizontally but a sharks’ breach is vertical. I thought vertically would be a better way to capture the action.

Essy raised his voice over the roaring engines. “We’re almost done”, he shouted as he started his turn. I jerked awake pressing my camera against my face with my last drop of energy. My shoulders ached. Without realizing it, I pushed the camera trigger just as the Great White breached in front of my lens.

Breaching

Truly, I do not know how I saw that shark breach. I caught it as it reached the peak of its breach with the dummy seal in his jaws.

When we brought the dummy back to the boat, Essy inspected the bites in the rubber and found one of the shark’s teeth. He handed it to me and I gave it to the youngest member of my team.

Your Thoughts